Running buggy firmware

I recently found myself in the position of debugging a firmware written in C. This firmware was running on a ARM Cortex-M4 with a fair amount of flash and RAM for a microcontroller. The source code amounted to around 10000 lines of code. The firmware relied on FreeRTOS and spawned around a dozen of tasks after initialization. It was also spawning a few more tasks from time to time that ran for short durations. With such amount of tasks, inter-task communication was a challenge and lots of locks were used, especially around shared resources.

During my first encounter with this firmware, it was mostly stable but strange bugs would appear such as corrupt data in ring buffers for no obvious reasons which would then cause other parts of the code to fail. It was really frustrating: the firmware was running fine most of the time but would then fail from time to time. To its credits, the code handled well bad situations and was often able to recover, yet this is not satisfactory.

How to find these bugs ?

I carefully analyzed the code manually and found a few bugs but I also looked for tools that could find any remaining bugs. I ended up using the following static analysis tools:

cppcheck is very simple to run on any project. You only need to give preprocessor symbols, include paths and source directory to analyze the source code. It is not very powerful but it is fast.

CodeChecker is a wrapper around clang static analyzer. It is slightly more complex to run as we first need to create the compilation database, then analyze the code. Fortunately, the documentation is good and commands are not too complex. Analysis takes more time than cppcheck though.

It is interesting to run different static analyzer on the same project because they report different warnings and errors. In my case, the project was not too large so it was possible to go through everything reported by static analysis tools. This is why, on small and medium size project, I think it is better to have too many false positive than nothing at all. In the end, it was a net positive to spend some time using these tools as I was able to find critical bugs such as several buffer overflows. However, even to this day, I am still not sure that this firmware is bug free despite spending several months fixing bugs.

Detecting concurrency bugs

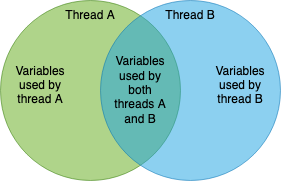

Concurrency bugs can only occur if the same piece of memory is used by more than one thread. Let’s assume we have two threads: A and B. If a variable is only used by thread A, then mo concurrency bug can occur and all reads and writes are safe. If a variable is used by threads A and B, then there is a risk of a bug everywhere we use this variable.

cppcheck and CodeChecker cannot find all bugs, especially concurrency bugs. Some tools already exist to ensure thread safety but they do not target small microcontrollers running a RTOS. On top of that, I did not have access to the hardware for a long time and could not run the firmware. Hence, any analyzer using runtime information to detect bugs were useless to me. I felt that there was a real lack of tools to detect concurrency bugs. Most of the literature focus on how to avoid bugs in the first place but, in my experience, bugs do occur regardless.

This was my main motivation for writing a tool that can detect concurrency bugs. It works by identifying all variables used by more than one task. Then, it warns the user of all occurrences in the code of those shared variables. It is up to the user to manually triage the output of this tool to determine if each warning is a bug or not. I think this approach is viable because the flash size on microcontrollers limits the firmware size. Hence, I do not expect this tool to run on large code base.

How do we find shared variables ?

The algorithm is quite simple:

- List all global variables

- Build call graph for all tasks

- For each global variable: check if it is present in the call graph of each task.

If a global variable is present in more than one call graph, then it is shared.

This is not too difficult to implement but it requires on using a parser for the C language. There are several options: cflow or sparse.

Reducing false positives

Once we have a list of global shared variables, we can start trying to cut down this list to eliminate obvious false positives. For instance, if a variable is only used in thread-safe functions, then no concurrency bug can occur. This is a common case for data structures such as queues or ring buffers. FreeRTOS provides such an API for queues.

Note that this tool does not take into account locks because it is not easy to determine for each statement whether a lock is acquired or not. To keep this tool simple, I chose to ignore locks.

Current implementation

This is still a work in progress. To get quick results, I wrote the logic in Python and relied heavily on existing programs. I am using cflow to build the call graph for each task. To find global variables, I modified a little bit smatch by creating a new check that analyses each expression and writes its results in an external file in JSON format. I have not published yet my work.

I am thinking about rewriting everything in C using only sparse. It would make a lot easier to distribute this tool but while I am still in an exploratory phase but this is not my priority.